When tracking storms on radar, some of the most visually impressive and complex looking storms are tornadic supercells. They often display certain radar characteristics. To the trained eye, these characteristics can tell a forecaster, or storm chaser, how organized the convection is, the structure of the supercell, and what the storm might be capable of producing. Below I provide some examples of common tornadic radar signatures and what they mean. All radar images were archived using the Gibson Ridge Level 2 Analyst (GR2Analyst) radar software package.

Types of Supercells

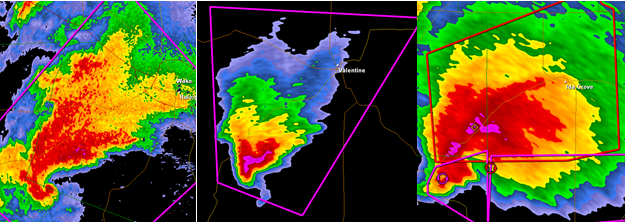

Before getting into specific radar signatures, it’s important to be able to recognize the three common types of supercells on radar: classic, low precipitation (LP), and high precipitation (HP). Classic supercells are the most common in the Great Plains, and also the most prolific tornado producers. Both visually and on radar, the rain free updraft area and precipitation core are separate.

Radar watching Basic tornadic signatures | Advanced tornadic signatures :: Forecast basics Identifying and understanding ingredients | Search for boundaries and gradients | Looking for what could go wrong :: Spotting basics Tornado shapes and sizes

A low precipitation supercell (LP) is simply a supercell that does not have a lot of precipitation surrounding it. Visually you can often see the entire updraft. High precipitation (HP) supercells are the most visually monstrous supercells on radar and in real life (though they’re often hard to fully see). These supercells have an abundant amount of precipitation, often occluding the updraft area and are the type that tend to have rain-wrapped tornadoes.

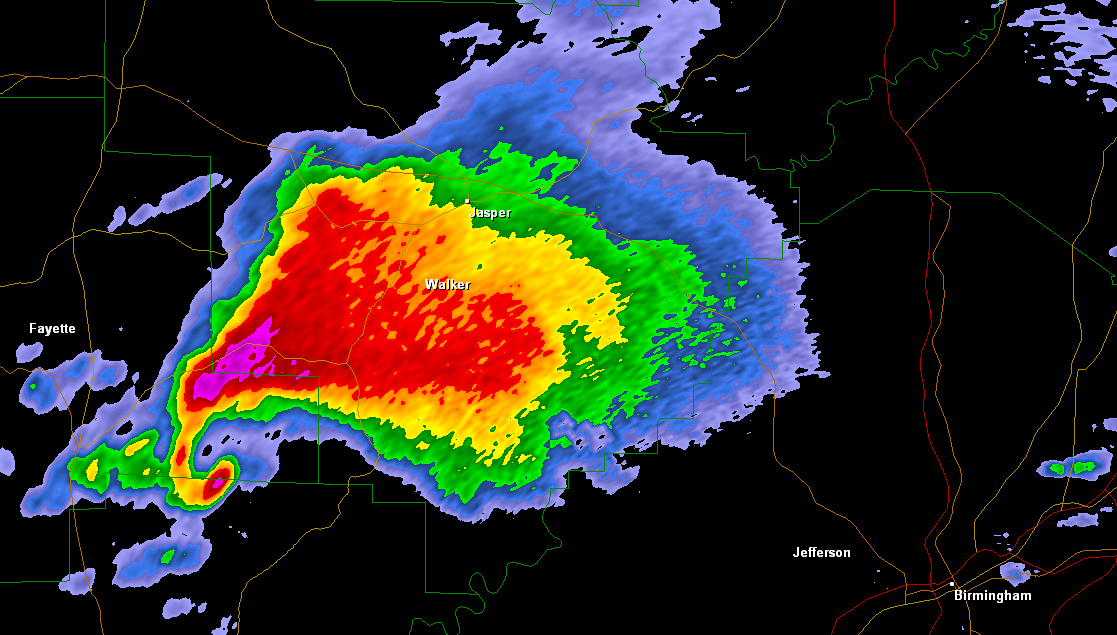

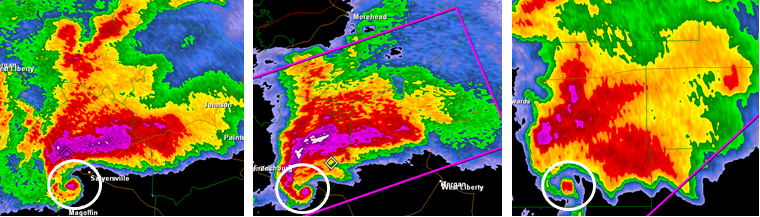

The Hook Echo

The most recognized and well-known radar signature for tornadic supercells. This “hook-like” feature occurs when the strong counter-clockwise winds circling the mesocyclone (rotating updraft) are strong enough to wrap precipitation around the rain-free updraft area of the storm.

Recognition of the hook echo has been around for decades; even before Doppler radar was invented and instituted in forecast offices, forecasters issued tornado warnings solely based on the visual appearance of a hook echo on radar. Disclaimer: not all tornadic storms display a hook echo and not all hook echoes produce tornadoes!

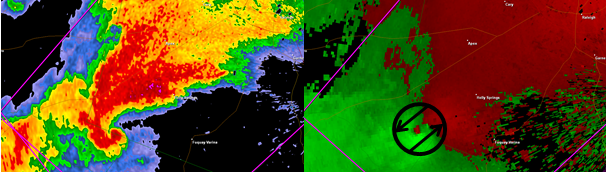

The Velocity Couplet

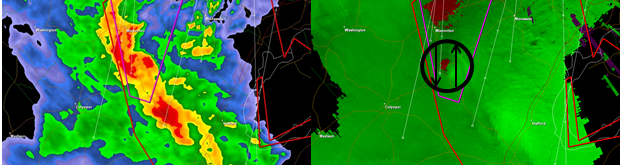

The previous radar images are base reflectivity images. The base reflectivity setting of the radar displays precipitation intensity: blues represent the lightest rain all the way to the reds and purples which indicate heavy rain and hail. The base reflectivity picks up “echoes” from the storm. A beam is sent out from the radar beam, hits the precipitation, and bounces back toward the radar providing information about precipitation intensity and type. The base velocity function of the radar does not show precipitation intensity but instead speed and direction.

Velocity is often symbolized in reds indicating winds moving away from the radar site (think “red shift”) and greens indicating winds moving toward the radar site. When bright reds and bright greens are next to each other, that can indicate rotation in a storm.

Using base velocity is extremely important when determining if a supercell is strongly rotating and poses a tornado threat. It’s even more critical with systems that are more linear but also produce a tornado threat, like a QLCS as one example.

As mentioned, not all storms exhibit that obvious hook echo and may appear considerably more harmless on the base reflectivity, when in fact they have strong rotation. Check out this example of a storm approaching Culpeper, VA on April 8th, 2011:

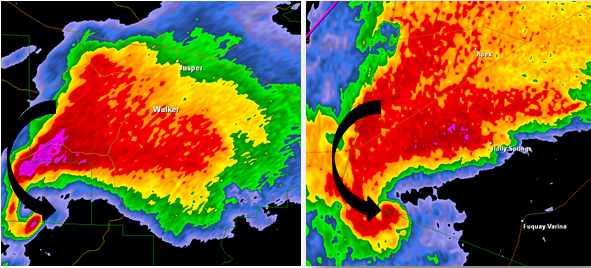

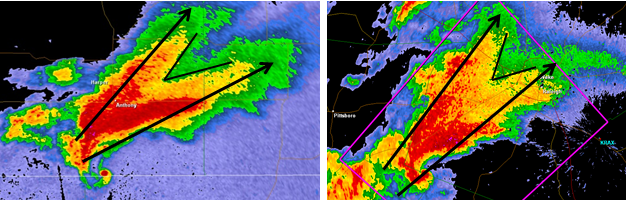

The V-Notch, or “Flying Eagle”

This radar signature does not necessarily foretell a tornado like the previous signatures, but it is usually only seen with the strongest and tallest of supercells, characteristics that correlate with those more likely to be tornadic.

The v-notch, also called the “flying eagle,” is a v-like pattern seen in the upper part of the precipitation shield (usually northeast of the hook echo area of the storm). This v-pattern occurs when the updraft of the storm is so strong, and the cloud itself is so tall, that upper level winds are forced to be deflected around the core of the storm effectively spreading the precipitation outward. A very cool signature if you see it on radar!

The Debris Ball

This is one of the more frightening tornado signatures on radar. A debris ball is exactly what it sounds like: the radar beam is sending back echoes of large debris lofted into the air by a tornado on the ground.

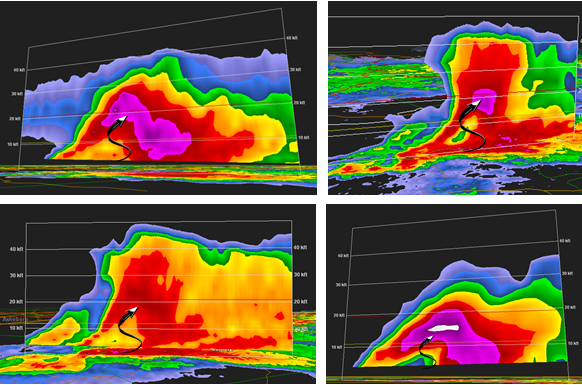

The Bounded Weak Echo Region (BWER)

Perhaps the most complex of the tornadic signatures. The bounded weak echo region, BWER for short and nicknamed the “elephant trunk,” occurs when precipitation wraps around the warm, moist updraft.

Precipitation cannot fall through the strong rotating updraft region of a supercell thunderstorm which causes the region of light to non-existent reflectivies surrounded by heavier precipitation which must instead blow around it. Same concept as the “hook echo” explained above, but we generally look for this particular feature using a vertical cross-section.

Conclusion

When following severe thunderstorms on radar, the signatures discussed above are a great way to figure out which supercells may be most intense or those most likely to be tornadic. It is important to stress that tornadic supercells could display all, one, or none of the above signatures on radar. Even non-tornadic storms sometimes show these characteristics on radar, which is why ground truth is so important in addition to radar interpretation.

Latest posts by Kathryn Prociv (see all)

- Halloween tornadoes: The spooky historical facts - October 28, 2013

- From domestic to international: Tornadoes around the world - July 25, 2013

- U.S. tornadoes that occur outside the U.S. … the continental U.S. that is! - June 26, 2013

I always wondered about the “flying eagle” echo. I first read about it in a National Geographic article about weather forecasting back in 1972. Later, I got some old literature from the weather service (it from the “United States Weather Bureau”, which showed a “flying eagle” on what appeared to be a range-height indicator type of radar. The caption indicated that echo was associated with a storm which caused significant damage in Kansas around 1960 or so.

Joel, that’s really cool you remember reading about the “flying eagle” echo. I suspect that like the hook echo, the flying eagle has been a recognized signature for a long time dating before Doppler radar. No surprise that storm you’re referring to caused significant damage. Supercell thunderstorms can climb upwards of 50,000ft. into the atmosphere, and storms that tall are the ones that produce large hail, intense lightning, tornadoes, and the eerie green sky you see sometimes!

Thanks for the well-explained information on tornadic signatures! There is tons of info online but the way you explained it is much easier to understand for a layman.

Hi Joni, glad you found the information useful and easy to understand! Happy to answer questions anytime.

I Didnt know if you knew of any good websites to use for forecasting that shows good radar like you provided in the examples. i am curently using intellicast for my own amature forecasting.

Thanks!

Kathriyn: Thanks so much for the great article… Good Pics + good images. If you don’t mind, I’m cutting and pasting them into my briefing for our county’s EOC and Sheriff’s office as part of my briefing to them. I’m a retired “Weather Weenie” and volunteer my services to our county.

Thanks! There’s going to be supercells in my county and needed to know how to correctly identify signs of tornados

I recently purchased an app “RadarScope”. Your explanation and photos make it so easy to understand what I am seeing on the maps. Do you have more articles or publications like this?

Thank you again for helping.

I live in central Oklahoma

I came upon this site as I was looking for what a tornado might look like on a radar. We just had a few minutes of really intense wind, and wondered if what I saw approaching my area would look like anything here. We were sitting in a v-notch (a small one, compared to these major storms you referenced!). I really enjoy watching the weather move through my area on radar. In another life, I might have studied this more and made a career out of it.

I follow the doppler radar very closely. I live in tornado alley (nebraskan panhandle) and we’ve had a particularily active year. I watch the radar simply to keep myself prepared. I’ve noticed alot of these signatures before, but none of them had tornadoes associated. In fact, before I ever read this article- I could pick out the flying eagle on a few separate occasions. I always thought it was odd and it imediately made me think “tornado”, yet no tornado happened from it.