Tornadoes have been in short supply to start off the year. The ones that have occurred have already been impactful, with both January and February containing killer tornadoes.

A relatively quiet start to the tornado year is not all that unusual, so that fact doesn’t mean much in itself.

There are a number of variables to look at for the months ahead to see if we can find any hints toward or more active or less active spring.

Details

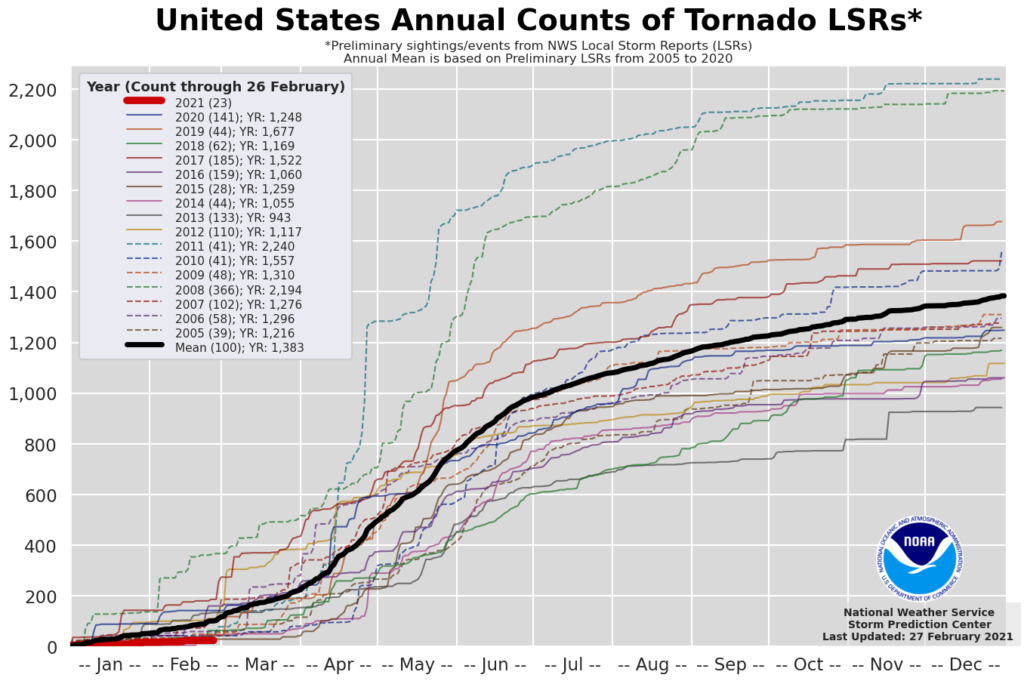

Even by winter standards, 2021 has gotten off to a quiet start, with just 23 tornado reports.

In comparison, the next lowest count in recent history featured 28 reports in 2015. February produced an active weather pattern across the continent, but it was dominated by cold air and snow, which allowed little room for the warmth and moisture severe thunderstorms and tornadoes crave.

So what’s to come in March?

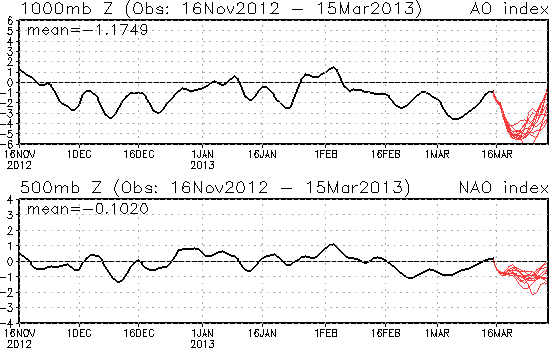

We can use a combination of ensemble models (mainly the GFS and ECMWF ensembles) and teleconnections to get a rough idea of what we may see in the upcoming weeks.

The Pacific North American pattern, or PNA, has one of the stronger, more consistent signals among the various teleconnections over the next two weeks. Generally remaining in a negative state, this would favor a cooler Northwest and warmer South.

This negative PNA pattern also generally leads to wetter than normal conditions across a good portion of the eastern U.S., but this correlation weakens the further you get into spring.

With the negative PNA being a more prominent driver of the weather pattern for the first half of March, we could end up seeing a more active weather pattern, but the medium-to-long range forecast does not necessarily allow the active weather pattern to lead into more tornado production.

The Climate Prediction Center‘s (CPC) 6-10 day forecast, which includes most of the first week of March, has a temperature pattern that ties closely to the negative PNA, but has better odds for drier-than-normal conditions across a good chunk of the central and eastern U.S.

This is more consistent with what the GFS and ECMWF ensemble models are forecasting for that period. However, a reversion back to a more typical negative PNA precipitation pattern develops in the 8-14 day both in the CPC forecast and on the models.

While much of the South and East sees drier conditions linger into the second week of March, there are indications that the storm track over the Plains and Midwest becomes more active.

All told, the first half of March is not shaping up to be an active tornado period. The lack of a major connection with the Gulf of Mexico and no notable east/west gradient in the temperature anomalies over the central and eastern U.S. should generally keep tornado activity lower than normal.

Heading into the back half of March, the CPC generally favors a continuation of the 8-14 day pattern. As such, we would likely see March end up with a lower-than-average tornado count this year.

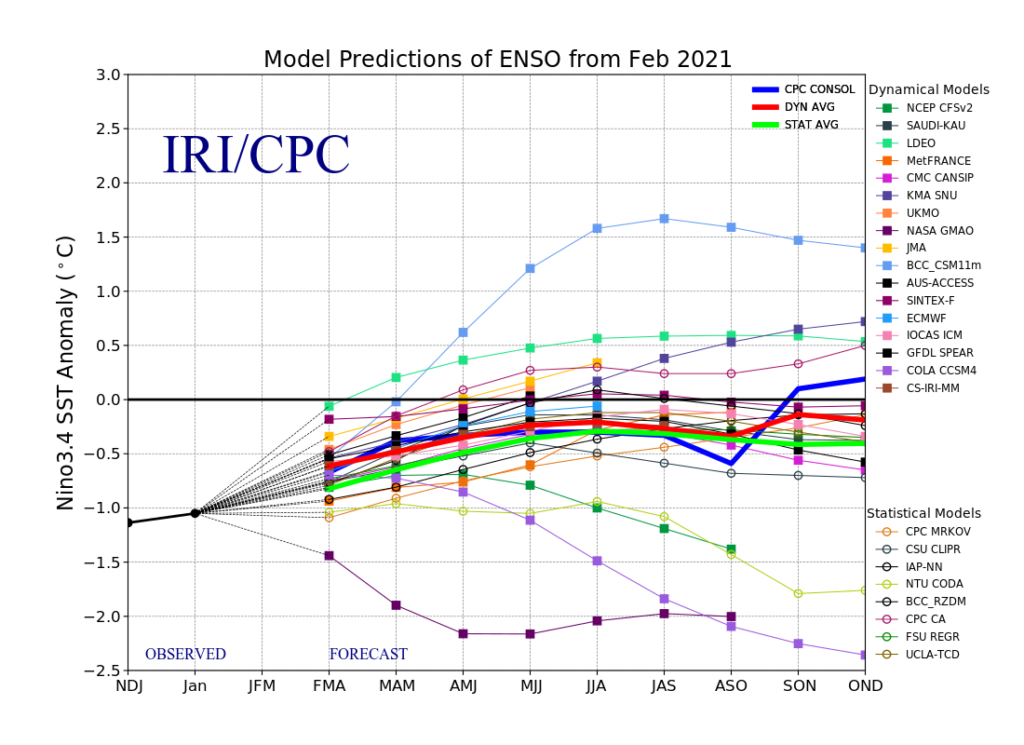

As we advance further into spring, we become more heavily reliant on longer-term signals like the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) to get a base for temperature and precipitation anomalies.

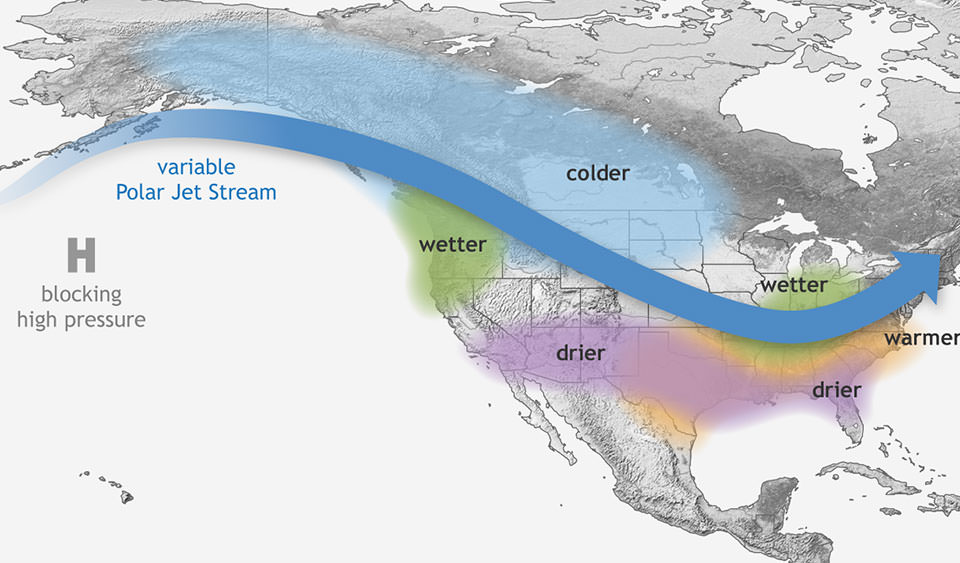

We are coming out of a moderate La Niña event and should trend toward a weak La Niña or neutral stage in the coming months. Below, the typical jet stream of a La Niña winter, from the NWS.

Aside from wetter-than-normal conditions in the Pacific Northwest, we are coming off of a very atypical La Niña winter. Warmer temperatures prevailed across the northern tier, while February saw record-breaking cold and snow in the south-central U.S.

While having a decent ENSO signal is usually helpful, is has been inconsistent at best this winter, which does not give me great confidence in the forecast as we head into spring.

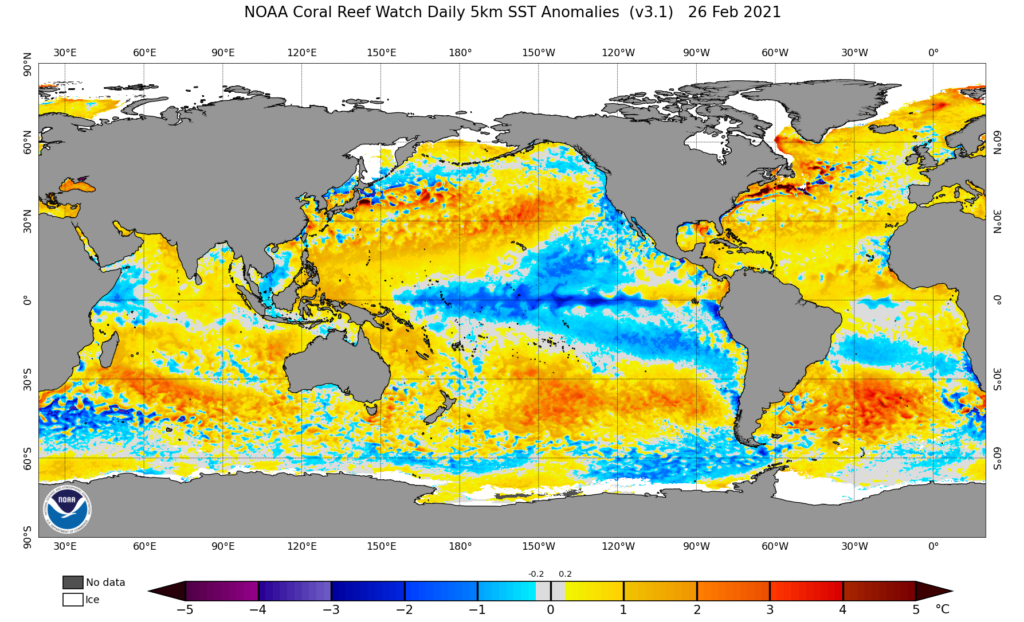

Sea surface temperatures can also give us a glimpse into the potential long-range weather pattern.

Often looked at in terms of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) and Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), we can see the AMO is in a positive phase thanks to a warmer Atlantic Ocean, while the PDO is slightly negative due to the cooler temperature anomalies along the Pacific Coast. While negative, the PDO signal is not all that strong thanks to warmer anomalies not far from the Pacific Coast.

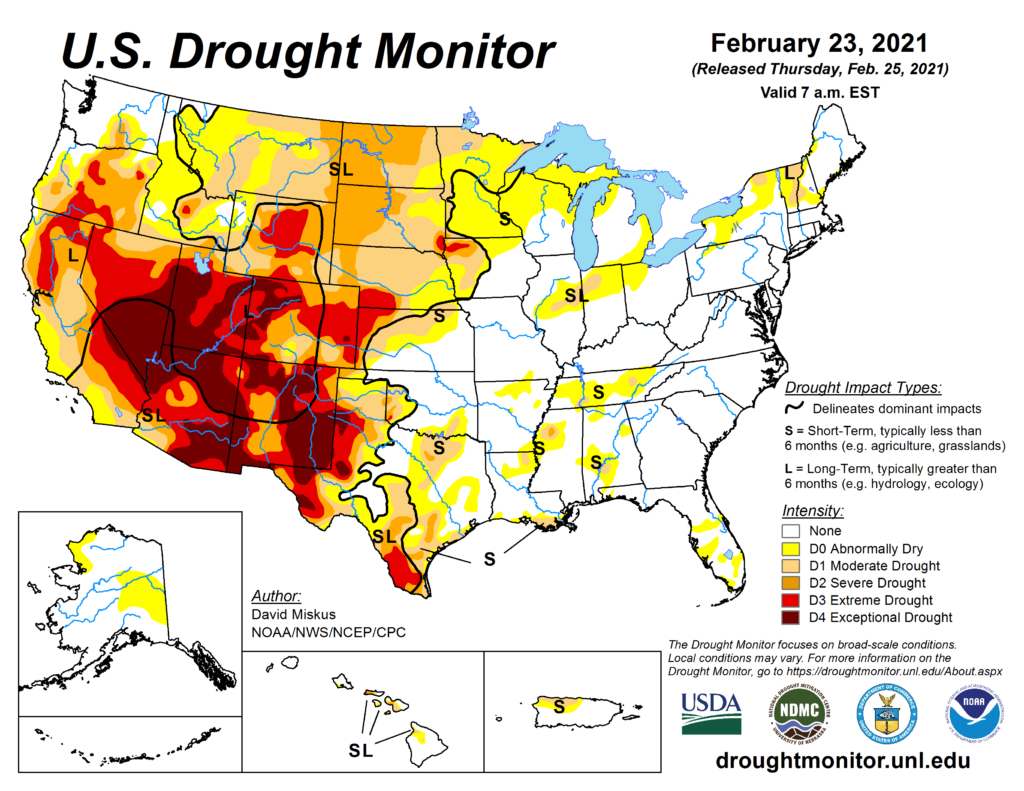

There are also significant drought conditions ongoing across much of the western half of the U.S., with little to no relief in the near term.

This could lead toward drier air overall this spring across key parts of tornado chase territory in the Plains. However, the main source region for low-level moisture east of the High Plains is mostly drought-free. These conditions could produce a more northern storm track due to warmer air over the Southwest, and the elevated mixed layer (EML) could end up being more pronounced, which may inhibit storm formation on more marginal setups.

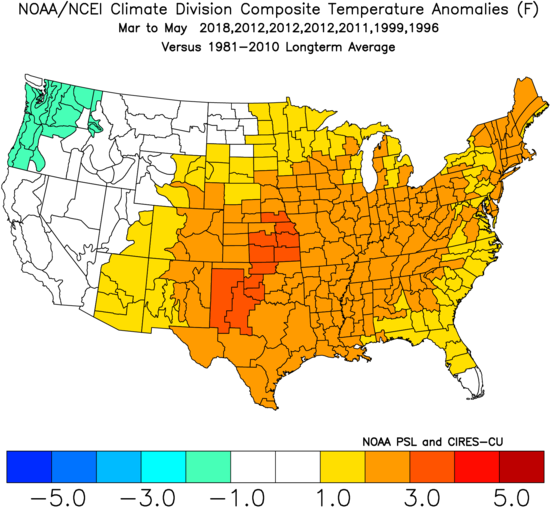

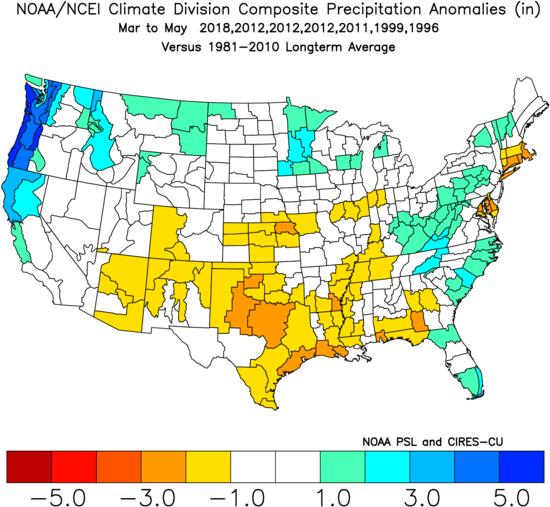

My analogs — 2018, 2012, 2011, 1999, 1996 — derived from a combination of long-range signals and recent patterns, shows a mix bag of tornado activity.

The historically-active 2011 season was included, but doesn’t carry much weight. From what I can see, 2012 offers a closer match to this year’s conditions, so it was weighed the most heavily. However, 2012 featured an active March for tornadoes, while some other analog years like 2018 and 1999 exhibited lower-than-average numbers.

Bottom Line

With an atypical La Niña winter and a mixed bag of signals and analogs, it’s hard to lean one way or the other for the overall tornado count relative to average. Most of the analog years ended up with a near normal amount of tornadoes over the spring season, and I am also leaning toward a normal level of tornado activity overall, despite what may be a quiet March.

Odds of the tornado count ending up below/near/above the normal off 511 tornadoes (1991-2010 average) for meteorological spring:

Below normal: 25% (less than 470 tornadoes)

Near normal: 50% (between 470 and 550 tornadoes)

Above normal: 25% (above 550 tornadoes)

Long term forecasts, while generally providing added value to climatology, are still very broad-brush outlooks and do not offer a very consistent level of skill. This forecast only hopes to capture some of the most reliable information available to provide a best guess as to what spring may bring.

Latest posts by Mark Ellinwood (see all)

- Spring 2023 seasonal tornado outlook - March 1, 2023

- Spring 2022 seasonal tornado outlook - March 1, 2022

- Spring 2021 seasonal tornado outlook - March 1, 2021