It’s the age of the wedge tornado. At least in reports.

The continued popularization of storm chasing, and weather as a whole, has brought certain geek words out front in recent times. Often, they are incorrectly used.

Forecast basics Identifying and understanding ingredients | Search for boundaries and gradients | Looking for what could go wrong :: Spotting basics Tornado shapes and sizes | Tornadic radar signatures

True wedge tornadoes — appearing at least as wide as they are tall — make up only a fraction of all types and shapes. Despite the seeming appeal to “run to wedge,” other terminology is largely intuitive and it helps everyone be better informed.

Related: These scary clouds are not tornadoes | Take a chill pill before hyping weather

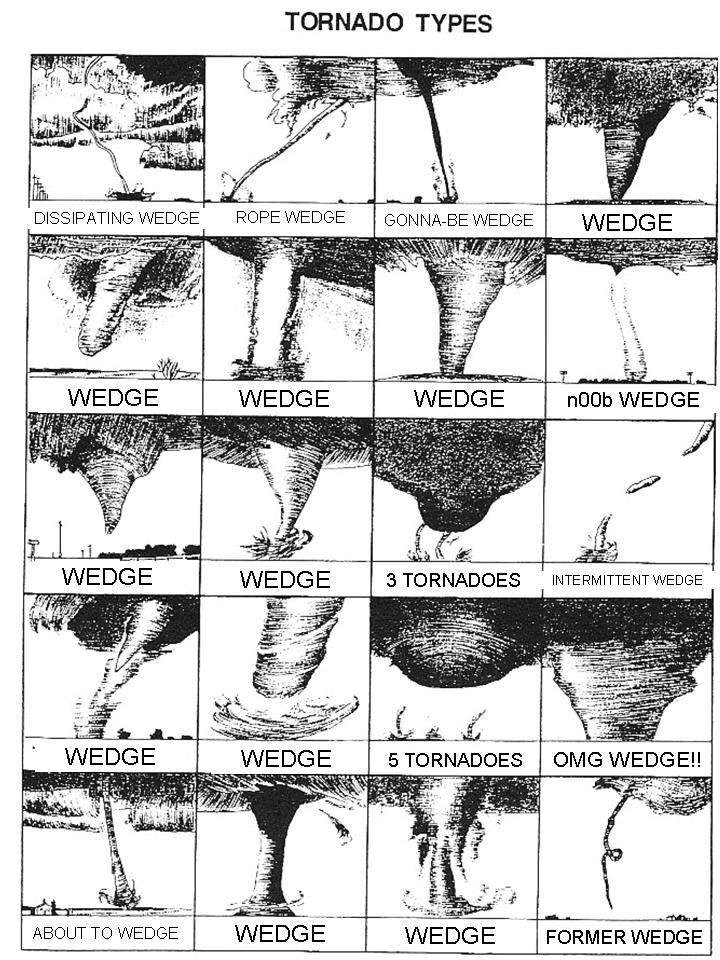

Amidst the overabundance of wedge reports lately, a humorous take on the tornado description crisis was posted by veteran storm chaser Dave Lewison:

Remember… a wedge is as at least as wide as it is tall.

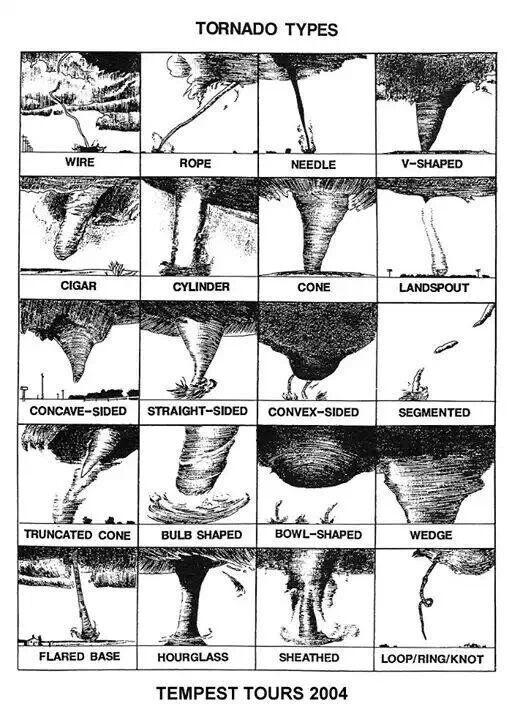

Sure, in the heat of the moment we’re not going to fault anyone for not measuring a tornado. But, now let’s look at the unaltered version and examine different ways we can describe these natural and dangerous beauties:

I can’t be quite sure of the original source above since I found it floating around Twitter, though it’s certainly possible that it’s Tempest Tours given the label. Regardless, it’s a true visualization of many of the various shapes and sizes of tornadoes seen in the wild.

Post-publish side note: Discussion in comments here, and also on Twitter, have led to the source of the original tornado type image! Storm chaser historian Blake Naftel points out that it originated with the first storm chaser, David Hoadley, and was used on a Tempest Tours shirt in 2004.

Of the 20 tornadoes in the unmodified image, only one is a wedge. And if we’re strict to the definition, it might be a bit friendly. Much less common than reports would often indicate.

Related: Tornado shapes and sizes | Tornado FAQ | Basic tornado types

So in the spirit of an expanding tornado vocabulary, and understanding that size doesn’t always matter, let’s look at some of the main types as seen on video:

Cone

Video: Dick McGowan

Cone tornadoes can be thought of as your classic twister. Widest where it meets the cloud base, it tapers as it gets toward the ground.

These are among the most well known tornadoes in the Plains, partly due to comparatively higher cloud bases than most tornado events further east, as well as much better visibility from distance. Usually, a true cone shape is transient as a tornado evolves. You can see that if you go back to the image up top, as it’s the same tornado later in its life.

Stovepipe

Video: HairyRusts22

As the name suggests, a stovepipe tornado is long and skinny. Having trouble? Think of a stovepipe!

Don’t let the skinny nature fool you, tornado strength is not dependent on width. The one above was part of a tornado event that produced EF4 damage (the second highest on the scale) back in June of 2014. As with many tornado types, this is often just a phase during the life cycle.

Drill bit

Video: HolyTornado.com

Not noted in the second tornado type graphic above, this has become a common term when it comes to describing tornadoes as well.

Arguably, it could be considered a stovepipe and it often is part of the roping out stage (see below). Drill bits are even skinnier than your typical stovepipe. It’s often used to describe a skinny but violent-looking tornado. If you’ve seen enough twisters, you can begin to tell differences in cloud-and-debris rotation speed. Drill bits might be little, but they’re full of fury.

Rope

Video: Shalyn Phillips

In its standard usage, a rope tornado is what is evident at the end-stage of a tornado cycle. They come out of tornadoes of all sizes, although not all tornadoes end as a rope. Some just quickly vanish.

Rope tornadoes can retain significant power, and even briefly gain wind speed as the circulation size decreases. In many cases, this is probably what is seen when folks use drill bit tornado terminology, so you can likely think of a drill bit as a visually intense rope.

Elephant trunk

Video: Tropmet | Storm Chasing

A fair amount of these tornado classifications are somewhat similar, or capture phases in between one dominant shape to another. Elephant trunks may fall into this category, but it’s easy to see why they are called what they are.

Some tornadoes have a full life cycle in an elephant trunk shape, and in some cases the horizontal part of the trunk is quite long. That lengthy horizontal can make tracking and viewing extra interesting!

Multiple-vortex

Video: TVNweather

It’s hard to say for sure that most tornadoes don’t have multiple vortices, but here we’ll focus on the ones with visible tendrils dancing around each other.

Multiple-vortex tornadoes can be weak or strong — they are always extra creepy and fascinating in appearance. The vortices often swirl around a center point, but you can see them move about throughout the entire rotation area, or even travel outside of it.

Satellite

Video: capbreak’s channel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRZi_mDqkxA

At first glance this may seem like a multiple-vortex tornado, but it is actually two separate tornadoes. In the example above, the smaller rope-shaped tornado is rotating around the larger parent tornado.

Satellite tornadoes are fairly unusual, although the frequency of satellite tornado reports has increased in recent times with increased storm spotting. They often exhibit anticyclonic rotation, which is also unusual in the northern hemisphere. Worth noting here: The Pilger “twin wedges” were not satellite tornadoes, rather they were likely dual or multi-vortex mesocyclone tornadoes.

Landspout

Video: TheF5hunter

Landspouts form under different circumstances than your well-known supercell tornado, or their QLCS-type siblings. Landspouts can form on or next to supercells. However, they are a type of tornado that is not associated directly with a mesocyclone.

Landspouts are commonly long, skinny tubes, often most discernible by the dust they kick up. Landspouts look quite similar to their over-water cousin the waterspout, and the processes in which they develop are somewhat similar as well. Landspouts frequently occur when no other large-scale severe weather is ongoing. They are most common in the High Plains, and shouldn’t be confused with gustnadoes which are not classified as tornadoes.

Rain-wrapped

Video: StormChasingVideo

This isn’t so much a tornado type as a tornado condition. A rain-wrapped tornado can be any of the multitude of shapes above, or whatever shape a twister can contort itself into.

Rain-wrapped tornadoes are often confused as wedges, partly because to “see one” you need to look into the abyss of a rain shaft. Sometimes no tornado is present at all, but the rain makes it appear as if there is one. HP supercells, QLCS, and squall line tornadoes represent a majority of the rain-wrapped tornado events.

WEDGE!

Video: TVNWeather

Big and fat. Often ugly. By the generally agreed upon definition, a wedge tornado is one that is at least as wide as it is tall. In 2015, it’s often any large tornado.

Wedge tornadoes are not always violent (F/EF4-5), but many of the most memorable violent tornadoes have been wedges. Just to name a few: Hackleburg/Phil Campbell, Alabama. Greensburg, Kansas. El Reno, Oklahoma.

Did we miss a key type of tornado? Let us know in the comments below!

Latest posts by Ian Livingston (see all)

- Tornado outbreaks: April, May and June peak-season primer - April 27, 2025

- Busy March for twisters to end with another multi-day event - March 28, 2025

- Everything but locusts: NWS shines in apocalyptic weather - March 17, 2025

The tornado types poster appears in the book “Under the Whirlwind: Everything You Need to Know About Tornadoes But Didn’t Know Who to Ask” by Jerrine and Arjen Verkaik. In the book, the credit for the chart says, “(adapted from Marshall, 1995)”.

Thanks! I kind of thought it was around longer than 2004. Thought maybe Hoadley made it but was having trouble finding a source. I’ll make a note in piece.

How about the tornado which doesn’t look like a tornado? As I recall from what I’ve read about the Tri-State tornado in March of 1925, relatively few people did not see a funnel. They only saw a wall of darkness moving across the countryside–and might have mistook it for a storm moving in. (There may be some debate as to whether the Tri-State tornado was even an actual tornado throughout its entire course–although the destruction it caused was certainly on a par with an actual tornado.)

Yes, could certainly add some on that. Was going to include gustnadoes but wanted to keep this tornado specific. May be worth addressing in the future. I do personally wonder plenty how tri-state would be characterized today on the path length at the least.. though it was undoubtedly a tornado or several.

Your definition of a “wedge” tornado is not exactly correct. A wedge is a tornado that *has the appearance* of being wider than it is tall. Bear in mind that the tornado vortex extends above the visual cloud base. And us old-time chasers typically required that the width of the tornado *at the ground* (the “bottom” of the tornado) had to exceed the distance between the ground and the cloud base. Given all of this, a wedge tornado is relative to the height of the cloud base. A narrower tornado is needed to be classified as a wedge if the cloud bases are very low to the ground. For higher-based storms, a much larger diameter tornado is needed to make for a wedge.

Finally, a wedge typically describes the largest of the tornado types. Thus, it seems redundant for folks to be saying “large wedge” or “massive wedge” unless the tornado is one whose base width is 2x or 3x or more the distance from the ground to cloud base. Those types are extremely rare.

Yeah, my bad there in the wedge section. Seems/seemed the ‘definition’ is rather loose so went looking for detail. Saw the SPC page after the AccuWeather page and didn’t update the wording. I think in this case the wording probably generally means the same thing though…

That is a good point to reiterate on cloud bases. I was recently trying to find out if there is an average cloud base height for tornado formation. Imagine it’s regionally biased with lower LCLs more common in the ‘jungle’ east of the Plains, though certain setups produce similar results no matter where they happen.

The last tornado example seems also to be a multiple vortex tornado, or perhaps a wedge tornado with small vortices orbiting it, to small to be considered true satellite tornadoes. Is it true that lot of wedges would be in fact be multipled-vortexed inside, their complex internal structure not being visible from the outside?

It’s not necessarily clear cut as a multi-vortex in the video at least in a classic sense. Those are more “horizonal vortices” in common description. You see them relatively frequently on very strong tornadoes, and sometimes on weaker tornadoes. I guess it’s a similar concept though I am not sure if they are necessarily the same.

But, I think it’s likely true that many (even most?) tornadoes have multiple vortices. Potentially even on a scale we don’t even really notice.