Long-track tornadoes are unusual in the tornado world.

Using a moderately restrictive 25 mile or longer path as the definition, they’re only about 2.5 percent of all twisters. In a more stringent 100 mile or longer path length, we’re looking at about 0.1 percent of the full modern record dating back to 1950.

For this discussion I’ll use 25 miles as a base, with additional looks at 50 miles or longer and 100 miles or longer tracks. In today’s lingo, you may hear the term referring to even shorter tracks, but we begin to wash the idea down heading much below 25 miles.

Not all long-track tornadoes are violent (F/EF4-5) tornadoes, though they do lean heavily toward the strong (F/EF2+) tornado side. Stronger than your average tornado intensity ranking. This seems fairly intuitive as one might assume a tornado on the ground for a long time is probably “better” than your typical short-lived tornado.

Related: Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale (SPC)

In the 1950-2013 modern tornado record, 80 percent of tornadoes are rated weak (F/EF0-1). But get to a track length of 25 miles or greater and there’s a reversal of fortune, with 80 percent of tornadoes rated as strong or violent.

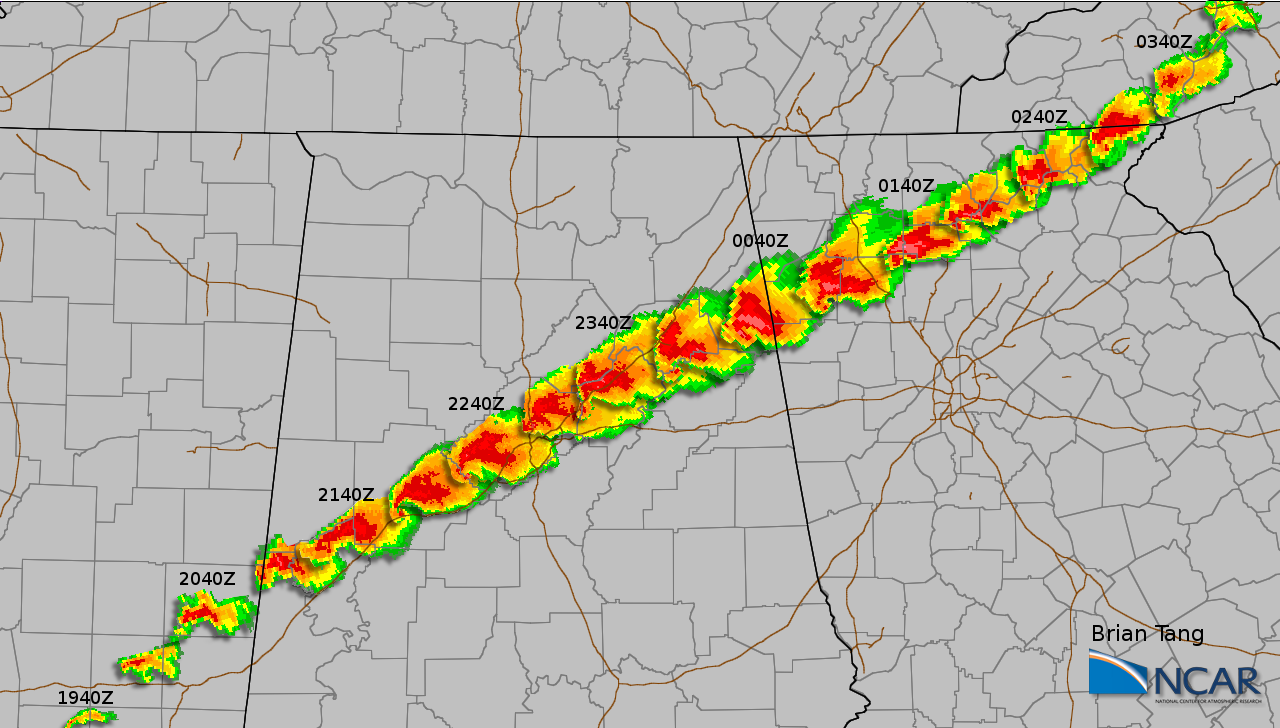

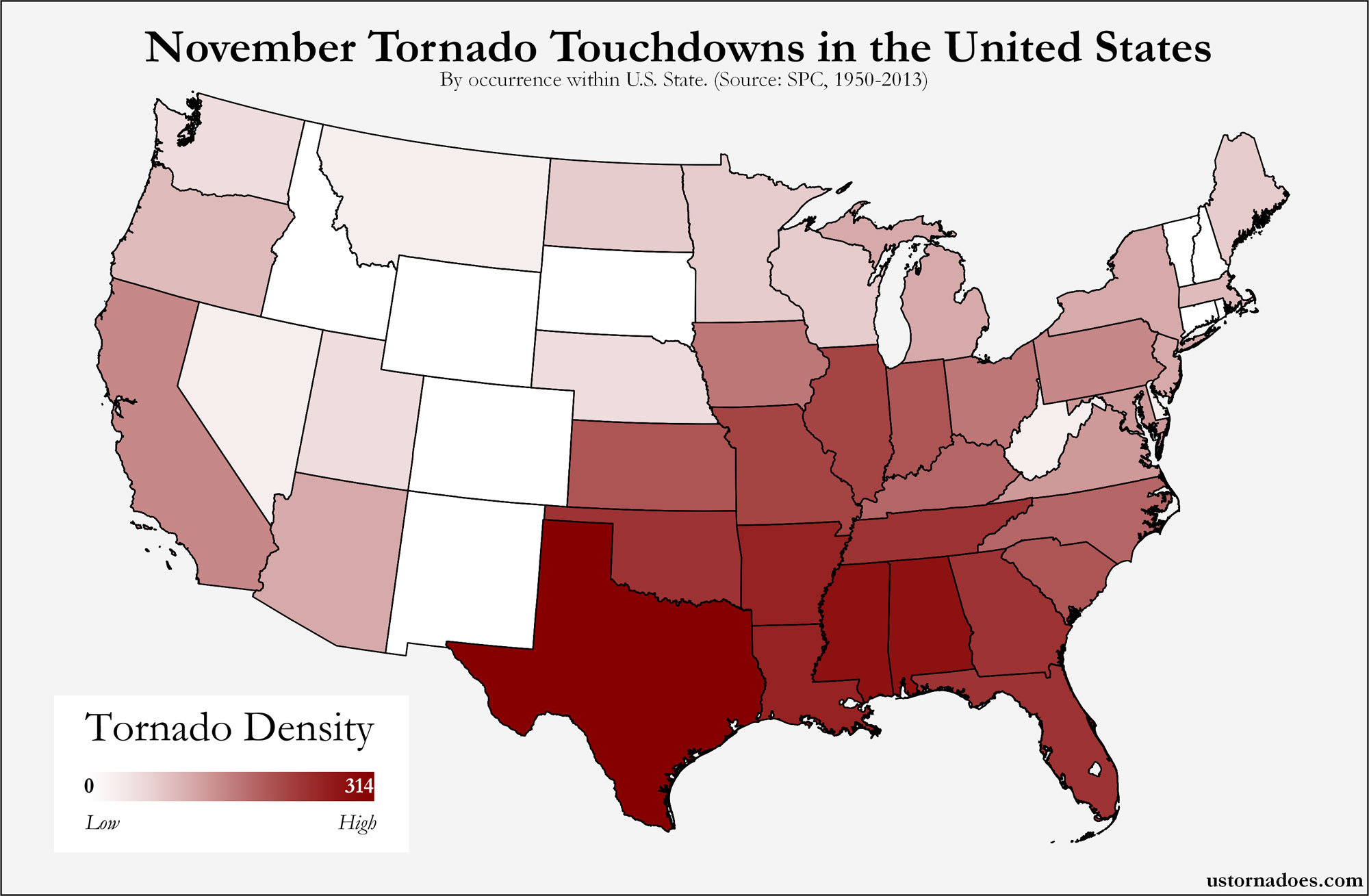

Long-track tornadoes are more deadly, too. That’s a lot of red (indicating killer tornadoes) in the maps above and below.

About 2.5 percent of all tornadoes since 1950 have caused fatalities. In long-track tornadoes of 25 miles or greater, the odds of deaths go up about 10 fold.

As you increase the track length, the potential for the twister being rated strong or violent rise, as do the chances that someone will be killed by the event.

Raising the bar to 50 mile or greater path lengths, over 35 percent of such tornadoes have ended up deadly. About 85 percent of this length tornadoes were rated as strong or violent.

100 mile or greater tracks are the F/EF5 equivalent of path-length breakdowns — in simpler words, very few occur. That said, there have been weak super long trackers, including two 0s. It’s also possible these tornadoes just managed to miss out on hitting much so their ratings remained low.

Otherwise, 90 percent of the 100 mile+ trackers have been strong or violent, and 50 percent caused deaths. Not something you want to face in your town, that’s for sure.

As mentioned in specifics above, long-track tornadoes are usually rated stronger than your average tornado. As an aggregate, they want to group in the F/EF2-3 range, and are relatively evenly distributed on either side.

There is also a noticeable slant to stronger and stronger tornadoes as track lengths increase. 2s are the most common in 25 mile+ tracks, 3s for 50+ mile tracks, and 4s for 100+ mile tracks.

So, key takeaways from long-track tornadoes include: They like to be strong to violent, and longer tracks lead to higher chances of deaths associated with the event.

Another is they often focus their ire on the early season into mid-peak. This is when steering winds are typically the fastest of the spring season.

We often think of peak tornado season as running April through June, with a number peak in May. When it comes to long trackers, the favoring of April is quite apparent. The “second season” bump is too.

Finally, by breaking down the numbers behind the maps above, we can take an educated guess at locations most likely to see long-track tornadoes.

In pretty much every map above, the central and northern Mississippi through Alabama corridor sticks out. It does in the bar chart showing touchdowns of 25 mile or longer tornado events as well. While the southern to central Plains states lead the way (hey Texas, you’re huge), Mississippi and Alabama are not far behind.

Additionally, as seen in the maps, when tracks get longer, the “stick out like a sore thumb-ness” of that Dixie corridor is even more pronounced.

Another main long-track region cuts north/south through the center of the Plains and then into the eastern Plains. Other high density areas are also scattered around, including in parts of the Carolinas and Midwest to Ohio Valley. Not many places are totally immune, though the center of the country is highly favored.

Latest posts by Ian Livingston (see all)

- Busy March for twisters to end with another multi-day event - March 28, 2025

- Everything but locusts: NWS shines in apocalyptic weather - March 17, 2025

- Top tornado videos of 2023 - January 1, 2024

I see that many of the strong and violent storms have crossed the Mississippi and other rivers, according to the first map. That should put down the nonsense about rivers and bodies of water protecting cities and towns.

I do wonder about how this data would look compressed differently.. as.. the rule seems to be that a longer tornado is deadlier.. but isn’t that obvious? A long track tornado does more damage because it exists longer.

I wonder how it would look if you, instead, broke down the data in some way to reflect deaths per mile, or some such…

Still, an interesting read!

Yes, I think it is true and/or should be obvious a longer track tornado has more opportunity to cause damage and/or death as well as to be rated ‘correctly.’ More or less presenting that the stats bear that out. I think there are other ways to further analyze the fatal aspect as you note.

It looks just about like you’d expect: violent tornadoes are very deadly, and F5s exceedingly so.

Average Fatalities Per Mile

F0: 0.0010

F1: 0.0054

F2: 0.0154

F3: 0.0657

F4: 0.3781

F5: 0.9749

Note that I made the scale logarithmic for easier display.

http://i.imgur.com/ns2ets7.png

I live about 20 miles west of Huntsville, Alabama, and I can attest to the fact that long-track, violent tornadoes are quite common here. Since 1974, 3 F5/EF5’s have hit my neighborhood. Incredibly, two of those tornadoes were 30 minutes apart! (during the first Super Outbreak in 1974). In 2011, an EF-5 came through, and was on the ground for 132 miles. Since 2011, I have seen 4 tornadoes from my front porch, and three of them were EF-3 or higher. It seems like northwest Alabama is a hot spot for tornadoes.

Does this trend change every 50-100 years or has it always been this consistent